Remembering Ontario Farmerettes – the history

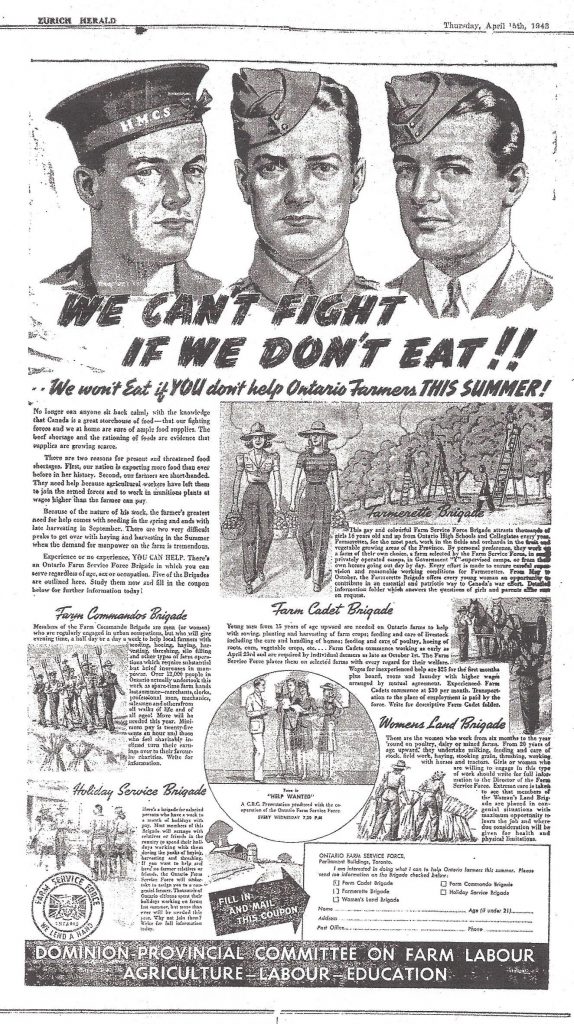

In November, we pause in our busy schedules to remember Canada’s war dead and those who have served in other military actions. But, we don’t usually stop to think about what went into keeping the troops going throughout their campaigns. They needed food. In fact, one of the messages to the public during the Second World War was, “We Can’t Fight If We Don’t Eat.”

When Canada went to war in 1914 and 1939, the loss of young men from farms and cities created widespread labour shortages even as the need for food and commodities increased to support Canada’s population, troops and allies. Women had no problem stepping up to fill the gap.

During the First World War, the national Soldiers of the Soil program appealed to high school-aged boys and girls. In Ontario, the provincial government established the Farm Service Corps for girls 16 and older to provide farm labour; the corps existed 1914 – 1918. Their work, explained in a Department of Public Works brochure, included “picking, packing, and shipping, weeding, hoeing, cultivating, gathering vegetables, pruning, spraying and tying up vines.” The young workers were called “Farmerettes.”

In the Second World War, the Ontario Farm Service Force initiated the Farmerette program in 1941 and invited girls to “lend a hand”; the program continued until 1953. Like the earlier program, girls were hired to work on farms from spring planting to the fall harvest. They lived in camps established by the YWCA, supervised by a camp mother. Some locations had tents, but others used high schools or empty motels. The girls were driven to and from the fields in whatever transportation was available—trucks, wagons or even makeshift car-truck combos.

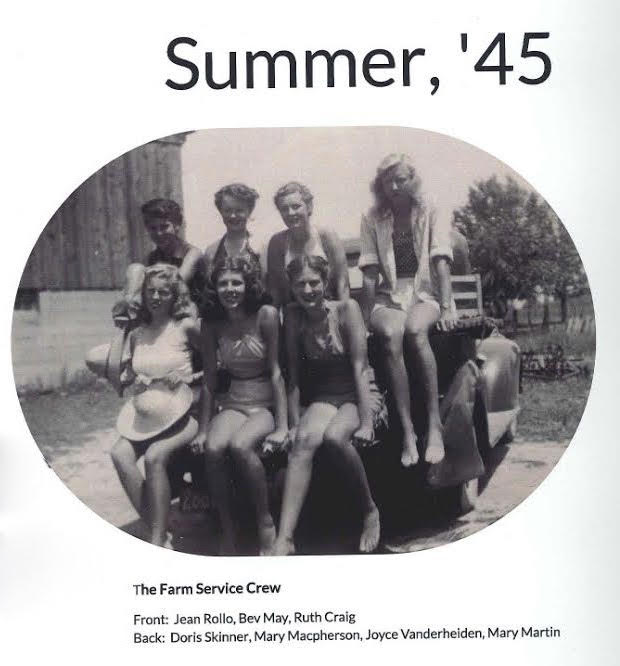

The farmerettes worked up to 10 hours a day, earning 25 cents an hour. If they were picking fruit, they made 25 cents per six-quart basket, or if pruning tomatoes, 50 cents per 250-plant row. Room and board cost $4.50 per week. In addition, tasks like weeding large plots of crop land, picking fields of corn and stooking wheat, they helped with meals and did their laundry by hand. Girls in grade 13 with good grades who worked a minimum of six weeks could be exempted from their senior matriculation exams. Bus or train fare to the camps was paid by the government, as was the return fare if they worked four months.

But the summer wasn’t all work, with its sore muscles, sunburns and bug bites. During the week, the girls went swimming after work, enjoyed camp fires, listened to music or played games with new friends. Weekends meant shopping in the nearest town, occasional weekends in Toronto for those close enough, or dances at the nearest dance hall with soldiers from a nearby army camp. Some met their future husbands. Many returned in following years. Most agreed they had the best summer ever. Women’s—and girls’—participation in the world wars proved that women could work as hard and as well as men.

Today, long after those wars, women play a vital role in agriculture. They still do the work they’ve always done—working fields, birthing livestock, keeping the books and taking an active role in farm management. But they also produce and market products, raise livestock and apply the technology and mechanization that have made farm work less physical.

In Canada, the roles of women on farms are evolving as more women enter agricultural careers. Women account for nearly 30% of all farm operators. They are more likely to raise crops than livestock and are mostly between 35 and 54. They are empowered and have formed organizations to support other women in ag production. When it comes to appreciating the growth of women’s contributions to agriculture, we should include the farmerettes of the two world wars.

When the Armistice agreement was signed between Germany and the Allied Forces on 11 November 1918, it signaled the ceasefire that went into effect at the 11th hour of that day. It also established Armistice Day, which became Remembrance Day in 1931. It’s a day to remember Canada’s war dead and those who have served in other military actions. It’s also a day when we can spare a thought for those who worked hard to support the country during the wars.

To learn more about Ontario’s farmerettes, read Onion Skins and Peach Fuzz: Memories of Ontario Farmerettes by Shirleyan English and Bonnie Sitter

More resources:

- Ontario’s Farmerettes: The True Story of Canada’s Forgotten Wartime Heroes from Readers Digest Canada

- Women at War from Veterans Affairs Canada.

- Women’s Work on the Land from Library and Archives Canada

Learning Activities

For educators, here are a few learning activities you could do with your students!

Good in Every Grain’s free classroom resources for teaching students about the Farmerettes

These free resources have been designed to enrich and deepen classroom learning, and include an introductory video, STEM challenge, discussion guide, cursive writing example, and more.

Learn MoreEmblems for Remembering

Emblems remind us and give us information. Businesses and sports teams have logos. Military personnel wear badges to identify their rank and work. We wear poppies in November to show we remember Canadian troops. The Farmerettes had their own emblems.

Think of how the farmerettes helped Canada during the world wars. Create an emblem to remember them.

The farmerettes of the First World War received a pin of the Farm Service Corps.

In the Second World War, farmerettes had a badge.

After the First World War, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae’s poem In Flanders Fields inspired us to wear a poppy.

Activities from Veterans Affairs Canada

Reading list

- A Poppy Is to Remember, by Heather Patterson. A story to explain to young kids why we wear poppies on Remembrance Day, with simple text and stunning illustrations. For teachers, there is a 5-page section about In Flanders Fields and Canada’s wartime and peacekeeping endeavours.

- In Flanders Fields: the Story of the Poem by John McCrae, by Linda Granfield. For grade 2 and up. John McCrae was a Canadian doctor who served in the First World War. He was also a poet and wrote In Flanders Fields. The lines of the poem are interwoven with information about the First World War and life in the trenches with maps and illustrations. Included for teachers: an introduction by Dr. Tim Cook of the Canadian War Museum.

- Canadian Instant Remembrance Day Activities. Grades K – 6 to help students develop an understanding of Remembrance Day.

Videos

- Remembrance Day. Charlie Brown and friends set out on vacation in France and go to Belgium to see where John McCrae wrote In Flanders Fields.